Chinese Americans

2008.041.009 Oral History Interview with Father Raymond Nobiletti

Father Raymond Nobiletti has served as Pastor of the Church of the Transfiguration in Manhattan’s Chinatown since 1991 and speaks Mandarin and Cantonese Chinese. Previously, he spent 15 years as a missionary priest in Hong Kong, where he had the opportunity to learn the language and be with the people on many levels through their problems and difficulties. Recently celebrating its 175th anniversary, Transfiguration, over the years, has welcomed waves of new immigrants. “We are known as The Church of Immigrants. Whoever comes through the door gets served,†he says.

Father Nobiletti was born in Brooklyn, New York, and grew up in the Bronx and Long Island. After high school, he decided to join the Catholic Foreign Mission Society of America, Maryknoll, and was ordained a Maryknoll missionary priest in 1969. Nobiletti felt very fortunate to be assigned to Hong Kong, which was his first choice. Initially assigned to Transfiguration in Chinatown only temporarily, Nobiletti found the pastor work so meaningful and interesting that he decided to stay. He notes that the Transfiguration parishship has been able to adapt to different languages and waves of immigrants, from the Dutch speaking to English speaking to Italian speaking to the Chinese speaking of various dialects. In the early 1990s, the ship, the Golden Venture, ran aground carrying 110 undocumented Chinese, mainly from Fujian Province. The church received a call from the police department because they did not have anyone who understood Fujianese. Six of the young people who were too young to go to prison were brought to the church, where Nobiletti got to know them better.

Over the years, increasing numbers of Mandarin-speaking Fujianese immigrants have come to Chinatown and have come to make up the majority of his parishioners. As a gua lo or foreign ghost who does not belong to any of the language speaking groups but knows something of Chinese language and culture, Nobelietti feels that he is able to welcome everyone.

2008.041.010 Oral History Interview with Anna Sui

Anna Sui is an internationally acclaimed fashion designer. Her hip, exuberant, original designs take you on a creative journey and mixes vintage styles with her current cultural obsessions. Whether inspired by Victorian cowboys, Warhol superstars or Finnish textile prints, her depth of cultural knowledge is always apparent. “When I am interested in something, I want to know everything about it,†she says.

Sui shares the memory of her first trip to visit her grandparents in China, where she became interested in mixing beautiful Chinese textiles into her everyday fashion. Her parents came from Europe and settled in Dearborn Heights, Michigan, where grew up in a typical suburban environment. Her mother studied painting at the Sorbonne, and her father studied architecture. Through them, she was exposed to a very international influence of culture when she was growing up. Through natural inclination, Sui began collecting images that she liked of movie stars, dresses, interiors, and hairstyles and began organizing them into folders and envelopes. She feels that she was meant to become a fashion designer. Everything in her personality, her accumulation of thoughts and inspirations, allowed for that.

Sui recalls the inspiration and thought behind two of her collections. The collection she did as a tribute to her Aunt Juliana drew what she remembered of her aunt’s tastes in textiles and her memories of her aunt and uncle’s wedding, in which her aunt wore dazzling qipaos with matching jewelry, shoes, and bags. Her Tibetan Surfer Collection was inspired observing the mix of styles of the audience backstage at the first Tibetan Freedom concert. Regarding fashion and appropriation, Sui believes that everything is influenced by something else and is always being reinterpreted.

2008.041.011 Oral History Interview with Frank Wu

Frank Wu is a civil rights lawyer, professor, and award-winning author of Yellow: Race in America Beyond Black and White. His book has become an essential text in Asian American Studies. He currently teaches law at Howard University and frequently lectures on civil rights law. “When I was a kid growing up, the last thing I ever would have wanted to do was talk about or think about race, ethnicity,†he recalls in this interview.

Frank grew up in Detroit, Michigan in the 1970s. His dad was an engineer at Ford Motor Company, which relied heavily on Asian workers for research, development and product design. He briefly discusses his experience of childhood cruelty on the playgrounds, and how the especially tough times in Detroit made it one of the hardest places in America to have an Asian face during the recession. He discusses how the confrontation leading up to the brutal murder of Vincent Chin in his city and how he or his cousin could have been the victim of this racial scapegoating and violence. It made him realize how words had the powerful to do damage but also to change the world. He reflects on dominant image of Asian Americans as the model minority myth, how it means that they should be submissive, passive, and deferential, and how it was first used to contrast Asian Americans with African Americans and other people of color. In his view, Asian American communities have generally not seen the importance of vigorous participation in democracy and the importance of making a fuss. His experiences as the first Asian American law professor at Howard University, the nation leading historically black institution, made Wu realize the importance of supporting other groups and sharing a common cause. Advancing civil rights, he believes, goes beyond self-interest and involves seeing that there are principles involved that affect others.

2008.041.012 Oral History Interview with Henry Yung Jr.

Henry Yung Jr. only very recently connected with the history of his distant ancestor, Yung Wing, the legendary writer, diplomat and first Chinese student to graduate from an American university. A fourth generation Chinese American, Henry attended Rutgers University and worked in the tech field. His late discovery is no less significant, as Yung Wing writing speaks to him with a sustained relevance even today.

Henry had little interest in his Chinese American heritage or familial relation to Yung Wing as a child, but his interest grew as he got older and read Yung Wing’s autobiography. Henry recounts some of this biography and notes that he was able to relate to a lot of his ancestor’s struggles and decisions at the same age. Wing was educated by missionaries in China and was later brought by them to America to continue his secondary education. He became the first Chinese person ever to graduate from an American university when he graduated from Yale in 1854. After graduating, Wing returned to China and held various government positions. Through the Chinese Educational Mission that he founded, he sent 120 students to study in the United States, however, political changes brought this to an end. By the end of his life, Wing did not have much wealth or power and was in fact in political trouble. Reading his ancestor’s autobiography, Henry thought it interesting how Wing could speak directly to him about his trials and tribulations in the United States and China and realized that he and Wing faced a lot of the same problems and difficulties. Henry addresses the stereotype that Chinese Americans are good at math and science and are good students and acknowledges that this might have helped him in life. He thinks that the one thing you could take away from Yung Wing’s story is that he made the most of the opportunities he was given. He concludes that young people will find a lot of value in learning about their ancestors and the problems they faced, as he did, as it helps give them perspective on their own problems.

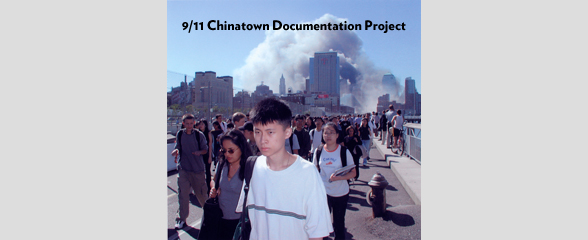

2014.036.002 Oral History Interview with Cambao de Duong November 17, 2003

Cambao de Duong is a Chinese-Vietnamese immigrant born in Saigon, South Vietnam to Chinese parents. Cambao grew up in a multicultural environment and learned to speak Chao Chow, Vietnamese, Cantonese, and Mandarin. He would receive a high level of education in Vietnam, and inspired by one of his principals, became an educator. De Duong would teach at the college level until he received an officer commission in the South Vietnam army. Given his previous service in the South Vietnamese government and army, he was granted refugee status and was quickly approved to relocate to the United States. When Cambao first came to New York City, he decided to work in a non-profit organization, where he assisted Asian immigrants with forms and vocational training. De Duong gradually became heavily involved with social work and community advocacy, becoming co-founder of the Greater New York Vietnamese American Community Association, as well as the Indo-China Sino-American Senior Citizen/Community Center. He makes observations of the changing demographics, crime rate, and sanitation of Chinatown during his decades-long involvement with the local community. De Duong shares his experience in Chinatown during the 9/11 attacks, and notes how similar it was to his experiences in the Vietnam War. He discusses the economic impact of the attacks and goes into detail regarding unemployment and increased requests for social services. Additionally, he observed that while the restaurant businesses in Chinatown mostly recovered two years after the attack, the garment industry will likely not recover.

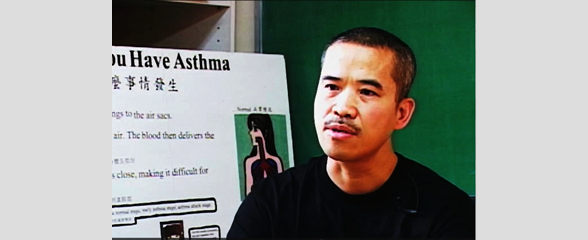

2014.036.003 Oral History Interview with Chris Chan May 24, 2004

Chris Chan is a Chinese immigrant who works for the Chinese Progressive Association (CPA). Born in China, Chris moved to Macau at two years of age following the Communist takeover of China. During his young adult years, he worked as a construction laborer in Hong Kong during the 1970s and 80s construction boom before being sponsored by his sister to immigrate to the United States in 1984. Chris describes the various construction and labor jobs he took on in the early years, the differences between New York City, Chinatown, and Hong Kong, and the challenges he faced as he tried to learn the English language. Chris would become active at the CPA in 1989 and would work for them as an employee in 1992. Chris elaborates on his work at the CPA, emphasizing its services to the local community, including but not limited to immigration rights, citizenship exam and procedure guidance, English classes, local environmental issues, and improving overall community health. In 2002, Chris and the CPA surveyed 580 people in the Chinatown area to study the effects of pollution on the local community and its correlation to asthma symptoms. He states that the CPA attempts to raise awareness of air pollution and dispel misconceptions of asthma in the Chinese community living in Chinatown through an emphasis on educating the population using their study. Chris notes that the 9/11 attack compounded the air quality issues but there are many pre-existing factors that needed addressing to improve quality of life. The discussion following his description of the CPA survey includes their plans to utilize the survey data to continue to educate the populace and to convince other organizations to assist in improving air quality in the Chinatown area.

2014.036.004 Oral History Interview with Jami Gong April 26, 2004

Jami (Jameson) Gong is a Chinese American comedian and local Chinatown resident. Born August 23, 1969 in New York City, Jami is the son of immigrant parents from Hong Kong and Southern China. His parents immigrated to the United States in 1967 with a desire for better opportunities and a better life for their children. He reminisces about his time growing up and living in Chinatown, the pollution problem, the changing demographics over time, and the education he and his siblings received. Jami continues on to talk about his time at Syracuse University and his eye opening experience as a college student meeting people from all over the world and being more independent living outside of Chinatown. Jami describes his early experiences doing standup during his time at Syracuse University and how it made him realize that comedy was a career path for him to consider. Jami would continue to do comedy on-and-off while working jobs in New York City until he came to a realization that he could do comedy in Chinatown as a way to revitalize the local economy and nightlife following the 9/11 attacks. The success of TakeOut Comedy and his Chinatown tours would be far reaching, with media coverage from international news groups giving Chinatown recognition as a result of his efforts. Jami also describes his own 9/11 experience of witnessing the towers fall and capturing photos and videos of that particular day. Following the attacks, he noted the negative impact it had on the Chinatown economy and worked to bring back tourism into the Chinatown NYC area through his work as a local tour guide and TakeOut Comedy events. His involvement in Chinatown led him to civil rights activism, leading the local OCA chapter to advocate for equal rights for Chinese Americans. He concludes the interview with his dreams of uniting the world through comedy and what he hopes to achieve in the near future.

2014.036.008 Oral History Interview with Joseph Chu, April 26, 2004

Joseph Wah Chu is a Chinese immigrant from Toishan County, Guangdong Province, China born in 1933. He grew up in Guangzhou and Hong Kong before eventually moving to the United States in 1965. In the United States, he worked in different cities such as San Francisco, Chicago, and New York City as a waiter and office worker. Joseph would eventually settle in New York City’s Chinatown, citing better job opportunities and existing friendships in NYC. In 1978, Joseph started working at the New York Chinatown Citizen Center, where he assisted senior citizens with applications for government benefits such as food stamps, Medicaid, and senior housing. He recalls the changes over time in Chinatown, from lowering crime to increasing difficulty finding housing for seniors. During 9/11, Joseph was taking a group of seniors out on a field trip. He recalls the transportation shutdown that made his group go to New Jersey to double get back to New York. He describes the reaction and also the impact of the attacks on the senior population. Joseph also talks about government assistance provided following the 9/11 attacks, which ranged from rent/business assistance to free air purifiers and air conditioners. The interview then turns to a discussion about Chinatown’s economic recovery and the changing senior demographics in Chinatown and concludes with a mention of ongoing issues related to housing.

2014.036.009 Oral History Interview with Angela Ng, January 20, 2004

Angela Ng immigrated to the United States in 1970 from Hong Kong and worked as a unionized garment worker for over 25 years. In the interview, she describes her work and experience as a garment worker, and talks about the changes happening in the garment industry. She also discusses union benefits, work conditions, family life for workers, pay, and job availability. On September 11th, 2001, Angela was working at the garment factory when she noticed a plane fly too low overhead and heard an explosion nearby. She recalls scrambling to reach out to family members and taking hours to get home due to the transportation shutdown. After the attacks, Angela describes the decline in work in the garment factory, loss of certain worker benefits, reduction of hours, and the change in workplace dynamics, specifically the decrease in worker leverage over factory owners as a result of a lack of garment orders.

2014.036.014 Oral History Interview with David Chen July 10, 2003

During the interview, David Chen discusses his experience as a Chinese American activist and director of the Chinese-American Planning Council (CPC), and his theory of activism. When Chen was younger, he rarely spoke. He would always wait for someone else to say the right thing, to which he would then agree. One time, as a younger student, he was forced to present a project because two of his partners did not show up. One of his classmates expressed how well-spoken he was and at that moment, Chen realized that his voice could be heard. Chen believes that in order to be an activist for peace and justice, one must see the bigger picture. Effective activism should start with institutions because that is how change can be enacted. He believes that anyone can be an activist as long as they talk, remember, observe, and are skeptical of organizations. He states that while spontaneous change comes from the bottom, sustaining change comes from the top, more specifically, from organizations. Chen joined the Organization of Chinese Americans in order to advocate for what he wanted to stand for and speak freely on those subjects. However, he also believes that a successful organizer does not talk too much because activism is about observing the smaller issues. As an activist, he believes that trust must be gained from individuals. Chen agrees that the Asian American rights movement was inspired by the Civil Rights Movement. Overall, he believes that society as a whole has become more willing to change and hopes that individuals, especially young activists, continue to act, give voice, and intellectualize.