Chinese American families

2008.040.008 Oral History Interview with Betty Sze October 25, 2007

Betty Sze discusses her vague memory of spending her early childhood playing outside of the Grand Machinery Exchange building, which was located on Centre Street. Her father owned a produce wholesale supply company, while her mother worked in factories. In her interview, she describes gentrification in terms of rent-prices consistently rising, developers becoming more aggressive in planning building projects, and entire neighborhoods such as Little Italy, being taken over by Chinese residents and businesses. Sze characterizes present-day Chinatown as a place that is more attractive to “Westerners†and inviting to tourists. She views tourism as having a positive economic effect on Chinatown, as well as contributing to the vibrancy of the neighborhood, but she also acknowledges that tourism has driven prices up and perhaps detracted from the authenticity of the Chinatown experience. While she has seen many of the special landmarks from her youth disappear from Chinatown, she still considers the neighborhood her spiritual home and an authentic Chinese American experience.

2008.040.019 Oral History Interview with Ho Ying Pang March 16, 2008

Pang Ho Ying was born in Taishan, China, but grew up and spent a large portion of his life in Hong Kong until he moved to New York with his wife in 1988. Interestingly, his family was divided on both the East and West coasts: he and his two brothers settled in New York, while his two sisters moved to San Francisco. Pang vaguely remembers his first impression of New York upon his arrival as relatively less modern than Hong Kong, claiming that Chinatown appeared backwards since it lacked the modern buildings and technology of Hong Kong. Regardless, Pang perceived Chinatown as a friendly and supportive environment that deeply valued family relationships and friendships.

Though Pang did not plan or arrange employment in the United States before immigrating, he trusted he would find a suitable job. After two months, he found work through his younger brother as a general handyman or “gofer†at the Music Palace theater. Pang eventually became the director of the theater and managed the daily operations until he retired. In his interview, Pang walks through the history of the Music Palace and offers his opinions on what ultimately brought about the movie theater’s demise in 2000. Pang asserts that the reason the theater went out of business was because it was no longer in demand after the popularization of the relatively cheaper videotape rental. As the theater began running deficits and attendance records started dwindling, Pang recommended to the Hong Kong based theater owners that the business close its doors, bringing an end to the last movie theater that specialized in Hong Kong cinema in the United States. Pang recognizes the pragmatic reasons for closing the Music Palace but still expresses regret that the theater could no longer serve as a community gathering place for residents and visitors alike.

Pang goes on to identify some of the changes that he has witnessed in Chinatown more broadly, particularly that many old buildings had been upgraded and renovated, empty and vacant lots had gradually been built up, rent prices had skyrocketed, and the general aesthetics of the neighborhood had improved. He also hints at a generational shift and ethnic tension, comparing the new wave of Fukienese immigrants with the older generation of mainland Chinese immigrants to the neighborhood. While Pang notes that his children do not desire to return to Chinatown, he still explains that he hopes to remain living in Chinatown because of its convenient location, the Chinese food and tea, and general familiarity.

2014.036.015 Oral History Interview with David Chen July 13, 2004

In this interview, David Chen discusses his work at Chinese-American Planning Council (CPC) as an activist in New York City Chinatown. Chen is the director of CPC, a private organization started in 1965 serving the public and focusing on low-income immigrant families, mostly Chinese. Services offered include language classes, translations, daycare centers, job training for adults, senior citizen care, childcare, and Meals on Wheels. Prior to his work at CPC, Chen worked for the mayor in Chicago. While there, he constantly questioned why there was no Chinese funding. While in college, Chen studied to be a social worker and community organizer. He explains that he was not good at chemistry and did not want to pursue medicine or law like his parents expected him to. During college, he and his friends volunteered in Chicago Chinatown, which is much smaller than New York City. In Chicago Chinatown, Chen and his friends taught English classes but there were not many job opportunities in the community, so he decided to work for the government. On a visit to New York City, Chen fell in love with how densely populated and large Chinatown was and was told that there were many job opportunities available. He applied for a position at CPC as a youth director twenty-three years ago, accepted the role, and moved to New York City. Chen was part of "Project Reach", which was an at-risk prevention program for troubled kids. He describes Chinatown as a transient neighborhood in that there is constantly an influx of Chinese immigrants every few years. CPC serves those immigrants by helping them get entry-level jobs and helping them get their foot in the door. By doing so, he hopes that secure immigrants who have gotten aid from CPC would be able to help the next wave. Asked about his upbringing, Chen shares that he is from an upper-middle class family and that his father was an engineer. He was originally born in Shanghai but his family moved to Hong Kong while he was a baby. He came alone to the United States during his final year of high school and focused on school in order to avoid being drafted into the Vietnam War. The last part of the interview briefly covers 9/11. Chen notes that in the recovery and aftermath, Chinatown was largely ignored although it was an adjacent neighborhood to the World Trade Center. Chen also describes how important Chinatown is to tourism because of its restaurants and shopping venues.

2014.036.015 Oral History Interview with David Chen July 13, 2004

In this interview, David Chen discusses his work at Chinese-American Planning Council (CPC) as an activist in New York City Chinatown. Chen is the director of CPC, a private organization started in 1965 serving the public and focusing on low-income immigrant families, mostly Chinese. Services offered include language classes, translations, daycare centers, job training for adults, senior citizen care, childcare, and Meals on Wheels. Prior to his work at CPC, Chen worked for the mayor in Chicago. While there, he constantly questioned why there was no Chinese funding. While in college, Chen studied to be a social worker and community organizer. He explains that he was not good at chemistry and did not want to pursue medicine or law like his parents expected him to. During college, he and his friends volunteered in Chicago Chinatown, which is much smaller than New York City. In Chicago Chinatown, Chen and his friends taught English classes but there were not many job opportunities in the community, so he decided to work for the government. On a visit to New York City, Chen fell in love with how densely populated and large Chinatown was and was told that there were many job opportunities available. He applied for a position at CPC as a youth director twenty-three years ago, accepted the role, and moved to New York City. Chen was part of "Project Reach", which was an at-risk prevention program for troubled kids. He describes Chinatown as a transient neighborhood in that there is constantly an influx of Chinese immigrants every few years. CPC serves those immigrants by helping them get entry-level jobs and helping them get their foot in the door. By doing so, he hopes that secure immigrants who have gotten aid from CPC would be able to help the next wave. Asked about his upbringing, Chen shares that he is from an upper-middle class family and that his father was an engineer. He was originally born in Shanghai but his family moved to Hong Kong while he was a baby. He came alone to the United States during his final year of high school and focused on school in order to avoid being drafted into the Vietnam War. The last part of the interview briefly covers 9/11. Chen notes that in the recovery and aftermath, Chinatown was largely ignored although it was an adjacent neighborhood to the World Trade Center. Chen also describes how important Chinatown is to tourism because of its restaurants and shopping venues.

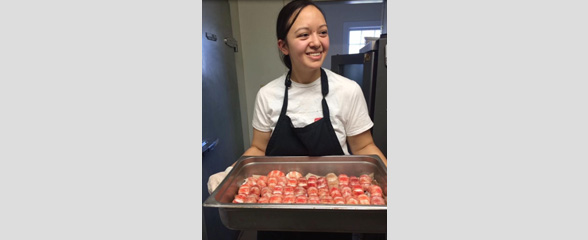

2016.037.018 Oral History Interview with Cara Stadler 2015/10/01

Cara Stadler is a third-generation Chinese American chef. She was raised in Massachusetts and grew up biracial in a predominantly white community. Stadlers love of food began during her childhood, when her mother would make a wide variety of Shanghainese dishes. While Stadlers culinary education began in her mothers kitchen, her career experience started in American restaurant kitchens. She worked under Marsha McBride at Cafe Rouge in Berkley and then Striped Bass in Philadelphia. As her passion for food grew and she realized she wanted to pursue a professional career in the culinary arts, she moved to France to hone her fine dining skills. Stadler studied the artistry and technical precision of French cooking while working at Guy Savoy and Gordon Ramsays Au Trianon Palace. Afterwards, she worked in different parts of East Asia including China and Singapore. During this period she launched the prive fine dining service Gourmet Underground in Beijing. Stadler returned to the U.S. in 2011 and collaborated with her mother to open her first restaurant Tao Yuan in Maine. They also later opened Bao Bao Dumpling House together. Stadler credits food for reconnecting her to her Chinese heritage. She expresses excitement at the growth of ethnic foods in the United States, noting that the American public is increasingly open to foreign foods and flavors. Stadler also underscores the importance of sustainability and ethical ingredient sourcing in the food world, and she adds that she hopes to contribute to positive changes in the industry.

2016.037.019 Oral History Interview with Wilson Tang 2015/10/30

Wilson Tang is a second-generation Chinese American restaurateur who was born in 1978 and grew up in Queens, New York. Before Tang was born, his parents decided to move out of Manhattans Chinatown to Queens to have a better family environment. Tang later found his way back to Chinatown when he attended college at nearby Pace University. After college, he went into a finance career, a path his parents strongly encouraged him to pursue. Tang quickly realized that the rat race of the traditional 9-5 job did not hold much appeal for him, and he began to consider entering the restaurant industry as his parents had done when they first immigrated during the early 1970s. Tangs first venture was a bakery opened in a building his father owned on Allen street. The bakery successfully ran from 2004 to 2007; however, success came at a steep price for Tangs personal health and well-being. Tang returned to the finance world in 2007 in order to regain control of his lifestyle and life-work balance. It was during this break from the restaurant world that Tang met his future wife and got engaged. In 2011 the opportunity to take over his uncle’s dim sum restaurant Nam Wah arose. More convinced than ever that the career of restauranteering was his true calling and despite the stress of his previous experience, Tang and his fiance decided to make the leap. The couple did some light renovations and refreshed the menu before opening, attempting to breathe new life into Nam Wah while preserving its historic atmosphere. As Nom Wah was renovated, Tang decided to create a Facebook page to document the long history of the tea parlor. The business received positive coverage from both the Daily News and the New York Times. As a result of this media coverage, business flourished and Nom Wah became a staple of Chinatown. Tang is grateful for the success he has experienced, but notes that the restaurant industry is still an incredibly demanding field. He hopes to use his success as a platform to elevate and support other Chinese American entrepreneurs and Chinatown businesses in NYC.