Gentrification

2008.040.015 Oral History Interview with Kam Mak March 6, 2008

Kam Mak is an artist who emigrated with his parents from Hong Kong to the United States at age ten in 1971. In this interview, he vividly describes growing up in an old tenement building on Eldridge Street and becoming involved with street kids during the seventies. He mentions the strong presence of street gangs during his childhood as well as the turning point during his youth that redirected him towards art as an escape from getting into trouble. Mak also discusses conceptual ideas that inspire his artwork, which is heavily influenced by his sensory impressions of the Chinatown neighborhood and culture. He notes the changes in neighborhood dynamic since then, observing differences in population, safety, and lifestyle. After moving out of Chinatown in the early 90s, Maks art became a means to reconnect or save his ties to the Chinatown community. He goes on to describe his work writing and illustrating his childrens book My Chinatown and designing a series of Lunar New Year stamps for the U.S. Postal Service. Reflecting on how Chinatown’s identity is rooted in its low-income and immigrant residents, he laments about how the forces of gentrification could eventually erode Chinatown to a “fake†shell of its former glory.

2008.040.016 Oral History Interview with Mannar Wong April 20, 2008

In her interview, Mannar Wong describes the changes she has seen in Chinatown spanning the past forty years. Emigrating with her mother and father from Hong Kong in the early seventies, Wong was raised in Chinatown and moved to Brooklyn with her parents in the eighties when she was a pre-adolescent. In the nineties, she later returned to the neighborhood she now refers to as “Chinatown Little Italy.†Wongs parents initially disapproved of her decision to move back into Chinatown, a place they regarded as a “starting point†for immigrants.

However, Wong considers present-day Chinatown “hip and appealingâ€, which she says was the partly the result of a community of creative types who renovated the area and acted as trailblazers for others to settle there. Wong classifies gentrification as, for the most part, making a place more desirable to people. Although, she warns that the question of whether gentrification is positive or negative is a loaded question – for instance, while she enjoys the appeal and “creature comforts†of the neighborhood, Wong predicts that she will eventually move out due to rising rent prices. Moreover, even though she does not consider herself an activist, she disagrees with small family-owned businesses being replaced by businesses that are not useful to the community.

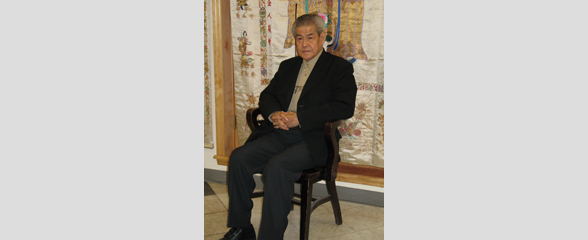

2008.040.019 Oral History Interview with Ho Ying Pang March 16, 2008

Pang Ho Ying was born in Taishan, China, but grew up and spent a large portion of his life in Hong Kong until he moved to New York with his wife in 1988. Interestingly, his family was divided on both the East and West coasts: he and his two brothers settled in New York, while his two sisters moved to San Francisco. Pang vaguely remembers his first impression of New York upon his arrival as relatively less modern than Hong Kong, claiming that Chinatown appeared backwards since it lacked the modern buildings and technology of Hong Kong. Regardless, Pang perceived Chinatown as a friendly and supportive environment that deeply valued family relationships and friendships.

Though Pang did not plan or arrange employment in the United States before immigrating, he trusted he would find a suitable job. After two months, he found work through his younger brother as a general handyman or “gofer†at the Music Palace theater. Pang eventually became the director of the theater and managed the daily operations until he retired. In his interview, Pang walks through the history of the Music Palace and offers his opinions on what ultimately brought about the movie theater’s demise in 2000. Pang asserts that the reason the theater went out of business was because it was no longer in demand after the popularization of the relatively cheaper videotape rental. As the theater began running deficits and attendance records started dwindling, Pang recommended to the Hong Kong based theater owners that the business close its doors, bringing an end to the last movie theater that specialized in Hong Kong cinema in the United States. Pang recognizes the pragmatic reasons for closing the Music Palace but still expresses regret that the theater could no longer serve as a community gathering place for residents and visitors alike.

Pang goes on to identify some of the changes that he has witnessed in Chinatown more broadly, particularly that many old buildings had been upgraded and renovated, empty and vacant lots had gradually been built up, rent prices had skyrocketed, and the general aesthetics of the neighborhood had improved. He also hints at a generational shift and ethnic tension, comparing the new wave of Fukienese immigrants with the older generation of mainland Chinese immigrants to the neighborhood. While Pang notes that his children do not desire to return to Chinatown, he still explains that he hopes to remain living in Chinatown because of its convenient location, the Chinese food and tea, and general familiarity.

2008.040.020 Oral History Interview with Paul Kazee January 6, 2008

Paul Kazee, one of the founders and former director of the organization Subway Cinema, played a significant role in showcasing Asian films to the New York public after the closing of Music Palace, a theater that specialized in showing Hong Kong films. Starting in 2000, Subway Cinema spent its first two years organizing events centered on dispelling what the group perceived as a misconception that Hong Kong cinema was degenerating and uninteresting. After gaining strategic connections and networking with NYU students, Subway Cinema achieved higher attendance which allowed them to began expanding to other Asian cultural films. The highlight of the organization’s work is its annual New York Asian Film Festival. The Festival generally lasts for two weeks and attracts large crowds of both Asian and non-Asian audiences, mostly comprised of students.

In terms of changes that have occurred in Chinatown, Kazee explains that he, along with numerous others, feel it is unnecessary to visit Chinatown now since much of the shopping available in Chinatown is now available elsewhere, particularly online. Kazee also reminisces about the pagoda-inspired phone booths, morning Tai-chi exercises in the local parks, and small local Asian video stores, all of which have gone by the wayside. Finally, he also briefly reflects on his feels towards gentrification, describing how he eventually realized how he himself contributed to the process of change in New York’s neighborhoods.

2008.040.021 Oral History Interview with Sio Wai Sang April 18, 2008

Sio Wai Sang sits down with MOCA to discuss his experience in Chinatown since he first arrived in the 1970s by way of Macau and the Dominican Republic. He discusses his experience working as a jeweler, how he set the precedent for immigrant jewelers in Chinatown, and how the counterfeit industry has negatively affected Chinatown businesses by making them all seem cheap. He also shares his thoughts on the more close-knit community culture of Chinatown when he lived there and how he perceives it to have changed over the past several decades as the different generations come and go. Mr. Sang also talks about how he believes Chinatown should move forward and develop by creating a Business Improvement District. He believes that it will improve the commercial side of Chinatown and leave the residential side unharmed because of the internal cohesion of the Chinese community which wants to keep Chinatown Chinese. He also expresses his belief that plans for development should be approached with a cautious perspective, so new developments don’t become too commercial and harm the cultural character.

2008.040.024 Oral History Interview with Cindy Lin February 15, 2008

Ming Xian Lin, also known as Cindy, tells MOCA about her experience immigrating to Chinatown from Shanghai where she had worked first as a farmer during the cultural revolution and then as a telephone operator. She discusses what Chinatown looked like in the early 1990s when she arrived, going into depth about her experiences working in different garment factories and her concerns about the crime in the area. Cindy also explains how the neighborhood has changed and offers some of her thoughts about gentrification and what she thinks the government and people in the community should do about it. She also shares her thoughts on the importance Chinese immigrants learning english and how she found her drive to pick up the language at 38 years old. She concludes by discussing how she hopes her family will remain engaged with Chinatown and the broader American world.

2008.040.025 Oral History Interview with Connie Ling February 12, 2008

Connie Ling, born in the Philippines and later a resident of Hong Kong during the 1960s, summarizes her experiences emigrating with her husband from Hong Kong to New York in 1967. Ling initially lived and worked in Chinatown, where she found employment as a machine operator in a garment factory. During her ten years working for the garment industry, Ling recalls an influx of Chinese immigrants and substantial growth in industrial businesses. After serving as a factory chairwoman for several years, she was eventually recruited as a union representative for UNITE in 1982, speaking for workers rights and mediating conflicts between workers and employers. At the time of her interview, Ling estimated that there were only approximately 100 union garment factories left. She attributes this decrease to the aftermath of September 11th, which caused commercial rent to double and garment industries to outsource labor to Sri Lanka, Mexico, and China. Ling also talks about the gentrification in Chinatown, stating that new condominiums are replacing old shops and factories while rent inflation is forcing old residents to move out of Chinatown. She goes on to note the growth among the Fukienese and Puerto Rican immigrant populations in the Lower East Side and expresses discontent with the growing number of Caucasian residents in Chinatown. Ling concludes by reflecting on how Chinatown’s garment industry is not likely to return due to significant changes in manufacturing and rent.

2008.040.026 Oral History Interview with Lana Cheung February 25, 2008

Lana Cheung emigrated with her husband from Hong Kong to the United States in 1987. Shortly after her arrival to New York, she remembers being initially surprised by the differences between Chinatown and Hong Kong, particularly in the contrasting architecture and combined residential and commercial areas. Cheung considers Chinatown a safe harbor for Chinese immigrants, where they had a sense of security and could speak their native language.

Cheung was employed by a Jewish import company, and later as a union agent for the garment workers union, UNITE (which had a Chinatown office starting in 1998). As a union representative, Cheung provides an insider perspective of the garment factory working conditions, which affected mostly Chinese immigrant women who endured long hours, hard labor, and the burden of sustaining their families. She notes that the garment factories also functioned as a place for women to communicate and socialize with each other, a detail that is often overlooked in historical accounts of garment factory working conditions.

Following September 11th, however, the garment industry slowed down and many of the garment factories were replaced by condominiums. While Cheung hopes that at least one garment facility will be preserved in memory of Chinatown’s industrial history, she otherwise welcomes the new developments and hopes that the younger and energetic generations will be a positive and reviving influence on community. Along these same lines, she acknowledges some current positive changes in sanitation, tourism, and efforts to ensure that Chinese culture and language are preserved in succeeding generations.

2008.040.027 Oral History Interview with Sing Kong Wong February 8, 2008

After being petitioned by his wifes family, Sing Kong Wong, a former administrator for a government agency in China, immigrated to New York in 1980 where he worked as a presser in a garment factory. Wong illustrates the poor working conditions in the garment factories, commenting on the lack of sanitation, violations of workers rights, and inadequate benefits and welfare. He explains how the steady decline in the garment industry has been especially problematic for immigrant populations, as they are unable to find other jobs and have limited financial means to pay the rising rent. Wong believes that the decline in garment factories began with the U.S. legislation that permitted jobs to be outsourced to Mexico, China, and India. After the events of September 11th, the situation worsened as landlords demanded higher rent and as zoning changed residential areas to commercial and business spaces.

Wong mentions that as a way to remember his past life and to share important life lessons with future generations, he has photographed personal and historically significant subjects and occurrences relevant to his life and experiences. Such subjects include the harsh conditions in garment factories, life in Chinatown, and the events of September 11th. He continues to describe the changes in Chinatown occurring over the past thirty years, like the improving tolerance and relationships between ethnic and provincial groups and the greater appreciation for Chinese culture and traditions.

Finally, Wong elaborates on his views regarding gentrification, worrying that people with lower-incomes will suffer the consequences of uncontrolled rent prices, eviction, real estate development, and a poor job market. He suggests that the government should be more involved in maintaining the parks, providing more recreational programs for the community, and fixing local traffic problems. Wong asserts that progressive and proportionate improvements are necessary, but these improvements must serve all residents and not just the wealthy.

2013.022.001 Oral History Interview with Anne Ho

Anne Ho is a longtime resident of Chinatown in New York City. Ho reflects on how her family moved to the United States and her early childhood growing up in Chinatown. She discusses the garment factory her mother worked at along with her daily routine living in Chinatown. She continues the discussion of garment factories by stating their importance of Chinatown during her childhood along with how Chinatown has changed overall. She then goes to discuss the development of Confucius Plaza and the types of people that lived there. Ho predicts how Chinatown will change in the future. She shares a story of going back to China and meeting her family. Lastly, she states the subjects that should be included in exhibitions and museum archives.